New Hunterian Museum display

Hunterian Museum Galleries

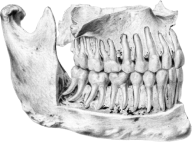

The Hunterian Museum is named after the 18th century surgeon and anatomist, John Hunter (1728-1793).

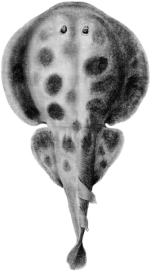

It includes the display of over 2,000 anatomical preparations from Hunter’s original collection, alongside instruments, equipment, models, paintings and archive material, which trace the history of surgery from ancient times to the latest robot-assisted operations.

The Museum includes England’s largest public display of human anatomy.

It includes the display of over 2,000 anatomical preparations from Hunter’s original collection, alongside instruments, equipment, models, paintings and archive material, which trace the history of surgery from ancient times to the latest robot-assisted operations.

The Museum includes England’s largest public display of human anatomy.